by Dolores Howard

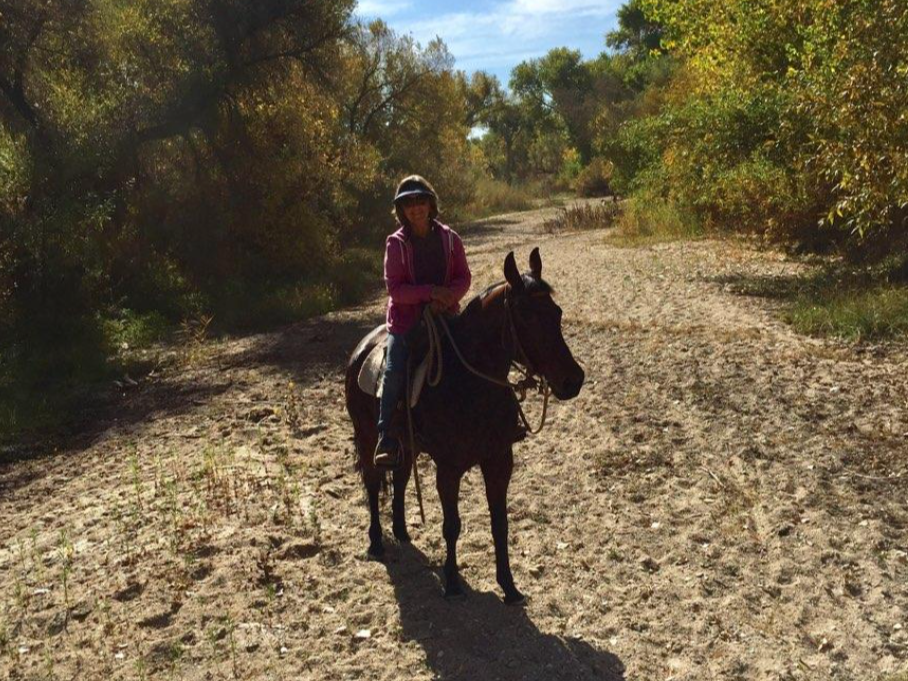

Editor’s Note: We are continuing our volunteer spotlight for the SLO Beaver Brigade newsletter, a feature to give folks an idea of who our wonderful volunteers are and how they’re making an impact in our watersheds. For this spotlight, Dolores Howard interviewed Ann Colby, who, along with her “wonder horse”, Stella, monitors beaver dams in the local stretch of the Salinas River.

Ann Colby is part of the San Luis Obispo Beaver Brigade’s inaugural team of beaver dam monitor volunteers, an effort that began in 2024 to enhance understanding and protection of the local beaver dam habitat. I’ve interacted with Ann Colby at various Beaver Brigade volunteer events, and she has consistently struck me as an individual that invites love and curiosity into all that she does and as a very smart person that I wanted to get to know better. Then, when I had the chance to interview her recently, from the moment the conversation started, because of her warmth and easy laughter, I felt like I had known Ann all my life. What follows is our conversation.

1. Thank you so much Ann for agreeing to have me interview you. Let’s start by you telling us a little bit about yourself, your background, how long you’ve lived in this area, and what’s important to you.

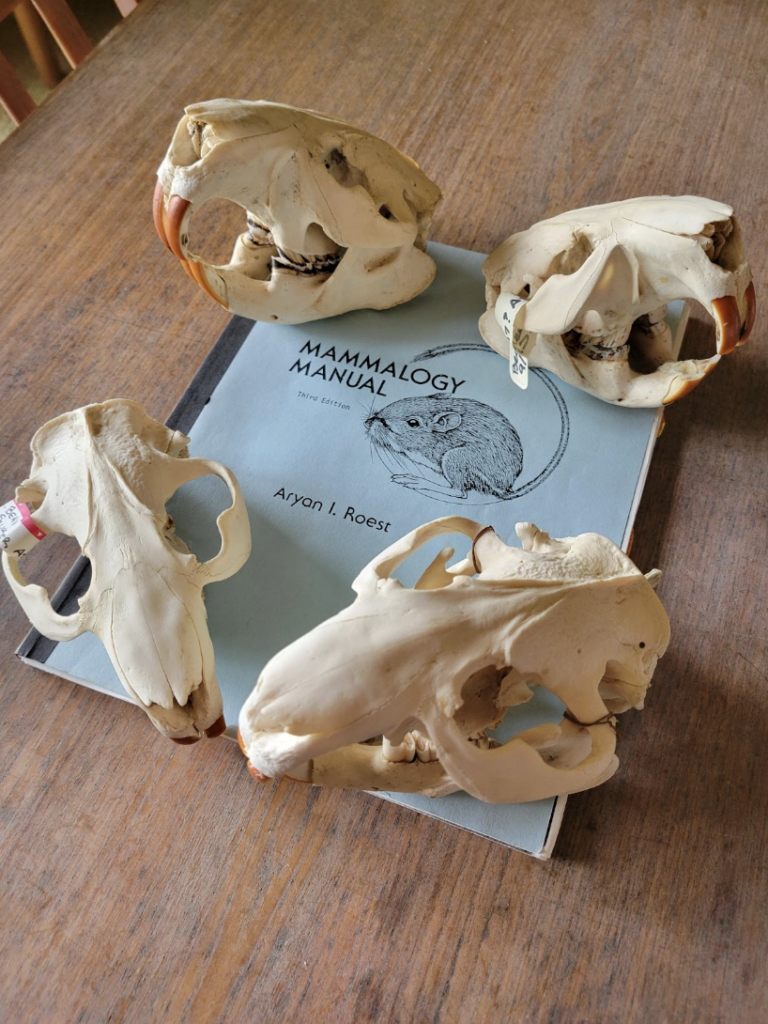

I moved to San Luis Obispo county a little over 25 years ago. Prior to that, I spent most of my life in the San Diego area, out in the countryside, in a home with a couple of acres, and a horse in the back yard. I became involved with an organization called Project Wildlife, which was licensed through Fish and Wildlife and I raised orphaned or injured raccoons at my home, bottle-feeding dozens of them and readying them for release. I moved up to this area to do a masters program at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, which led me to becoming a licensed therapist working for the County of San Luis Obispo in offices in Paso Robles and Atascadero. I had been actively involved with horses and with raccoons, which are such mischievous creatures, so once I moved, I got to thinking about what I could do that would be related to wildlife. I believe that beavers and raccoons are very similar in their personalities, curious and resilient, so for me there was a natural connection there. After retiring a few years ago, I used the newfound time on my hands to regularly ride my horse up and down the river bed, exploring. As local (Atascadero) horseback riders know, the Salinas riverbed is almost the only place around here to ride horses without going out to the coast. Now, I already kind of knew about beavers because back in 2006 I found a beaver skull in the riverbed. Yes, a beaver skull! I’ve always collected bones and things, but I only scavenge things that have died, as “do no harm” has always been my primary mantra. When I found the skull, I put it in a plastic bag on the back of the saddle and took it home. I thought it was a beaver because of its long teeth, but everyone that I showed it to would say “No, that’s impossible – there are no beavers in this area.” Back when I was at Cal Poly, I often perused the books in the Cal Poly bookstore and I found and kept a mammal identification booklet for one of the science courses, written by a professor who has since retired to Los Osos, I believe. It was concise and precise, and it told me unequivocally that this was a beaver. So, I figured that at some point, I would meet someone who understands this and we would compare what we know.

2. So then, after having a positively identified beaver skull for some years, how and when did you first become involved with the Beaver Brigade and what kinds of activities have you participated in?

A few years ago, I read an article about the San Luis Obispo Beaver Brigade in a local newspaper and due to my conviction that beavers were here, I knew that I needed to meet this group of people. A few days later, during one of my regular rides in the river, I spotted two people wandering around, poking around really, in the riverbed, but appearing to do so very purposefully. They kept waving at me and I could tell that they wanted to see my horse. I said to myself “I’ll bet they’re with the Beaver Brigade,” and sure enough, it was Fred and Kate from the Beaver Brigade. They were thrilled that I had learned about the Beaver Brigade from the newspaper article. Kate encouraged me to get involved with the periodic trash cleanups in the river. She was wonderfully persistent about getting information to me about the cleanups as they were being scheduled, and so I joined them. I actively participated for a while, and then I went on a Beaver Brigade Watery Walk. The Watery Walk was an excellent way for me to pick up knowledge about beavers, exactly what I was looking for. Then I began to find out about the studies that Dr. Emily Fairfax and her students were doing in the Atascadero portion of the Salinas, and so I started to learn more about beavers. Finally, my hunch had been validated: beavers really are here. Oh, but I need to tell you that since that first skull, over the next few years I had found 3 more, and then found a full-sized beaver skeleton, which I also took home with me on the back of my saddle. No wonder I ride alone! Who would want to ride with someone with a stinky beaver skeleton hanging from the back of their saddle?

3. That is both hilarious and fascinating Ann! While you’re at it with your storytelling, can you describe any changes that you’ve witnessed in the Salinas River watershed and why those changes are important for you personally and the community?

I’ve seen huge changes, in both positive and negative directions. The funny thing is that my favorite part of the river now was the part that I didn’t like at all before. When I rode through that part, the baking summer heat and dry river bed felt awful, I didn’t enjoy that part of the river at all. I often thought, “Why does anyone want to be here?” But that dry riverbed slowly gave way to a wetter and wetter, and lusher part of the river that today is home to more and more birds – snowy egrets, great blue herons, ducks and more. My friend and I started calling this part of the river “Water World”. In the hot summers, when you get down into the riverbed, you can feel the temperature drop 10 or 15 degrees. Now, what if our whole Salinas River were this way? These changes began seven or eight years ago, but the biggest changes have been in the last three or four years. But funny enough, this has changed my horseback riding! Now I can’t ride a continuous trail through the river because there’s so much water! I need to use detours and roads that are not very safe for horseback riding. So the win for wildlife is a bit of a loss for horses. That’s why I’m working on revisions for trails and continuity of access for hikers, dog walkers, bicycle riders and horseback riders, that is, folks that will travel quietly, with low impact, in the river.

If people slow down and observe nature and the wonders in the river, they will see different things than if they are going fast. Getting to know the river takes time. Over the last three or four years, we had been seeing a number of active dams. Then in the last two years, these dams were destroyed by the flood stages of the river, but lo and behold, the beavers started rebuilding and here they are, back again. Beavers are the comeback kids of all time. But this is why a quiet and slow presence in the river is so important. You can go through the river quickly or at the wrong time and not see anything. But, if you go slow enough and often enough, you’ll see the changes. My eyes are getting trained to see the changes. I’ll see a beaver structure just beginning to appear and I know that I need to come back in a week or two and document the changes. It’s so much fun. Occasionally if I skip a week, I am so surprised to see what they’ve done, and their structure can be twice as high as it was on my last visit. And I am a witness to this!

We have seen incidents of destruction from off-road vehicles, where water that was previously held back is flushing through a destroyed dam; in spite of that, the beavers demonstrate their resilience. Within a few weeks they build again, a little differently, adapting and changing their approach.

4. Can you talk about why you decided to become a beaver dam monitor volunteer? Also, how do you see your role as a horseback rider in monitoring the Salinas River?

Trash cleanups are very important to the health of the river, but they weren’t helping me to learn about beavers. I needed the personalization and enthusiasm I get from more direct involvement with wildlife. When the Beaver Brigade first put out a notice that they were looking for volunteer dam monitors, I thought, “That’s what I am already doing!” However, this would now be a way to report and share what I was finding.

There are many advantages to being on horseback while monitoring the dam. I can really cover ground and I can see more things by being higher up. And, I don’t have to walk through all that deep sand. Readers of this interview might not know that when I’m on my horse, wildlife doesn’t see me as a human because the smell of my horse camouflages my scent. For this reason, I’ve been able to see bobcats, coyotes and all sorts of wonders. I can walk up carefully and quietly on my horse, and wildlife just carries on.

5. Ann, I never realized that riding a horse changes the interaction between the rider and nature. That’s amazing! Can you share some of the experiences you’ve had monitoring the beaver dams?

I’ve had many, but I’ll share one. One day early on in monitoring a newer dam, I ventured further than I usually go, and as I came around a bend with big bushes, my horse alerted me to the presence of something, with her head up and ears forward. I have learned to look in the direction that she is looking when she does this, and there, directly in front of us in the sand, was a large bird with something, a kill, in its talons. I told myself “There’s no time to get your camera out,” so I just tried to completely absorb what I was seeing. I fully expected it to be a common turkey vulture, but quickly realized it was a bald eagle, just 20 feet in front of me! Many of us know that there is a pair of bald eagles nesting in that area. This one was immediately in front of my horse and I didn’t know what either one was going to do. I knew it would take off and possibly the horse would bolt, but I expected it to try to veer away from us. It gathered itself to take flight and took off, but came directly towards us, just clearing over our heads by about four feet. I could hear the whoosh of the wings as it flew over us! I believe that since my horse saw the bald eagle begin its flight, she knew that it was trying to get away and so she was not spooked. (Plus, she’s just a remarkable trail horse!)

In a moment like this, you feel so at one with nature: I’m part of this picture, my horse, this bald eagle and I are having this moment together. And no one was trying to hurt anyone. We were in peaceful co-existence. This is what happens when we approach nature with calm and respect.

6. What do you like about being a Beaver Dam Monitoring Program volunteer and what are your hopes for your future participation in this? What are some needs for the program that you can see?

The group of volunteers that work together to do this monitoring is a stunningly dedicated group of people who are willing to learn anything, read up on beavers and document what they observe in the river. It would be great if we begin to acquire a common language and process for documenting the changes in the river. This common language may already exist or we may have to create it. For example, recently I was heartbroken to find that a dam had been destroyed by vehicles in the river. But in the days following that, I began to see a half-circle dam forming in a location near the dam that had been knocked down. The water was ponding up behind this half-circle. When there was a good sized pond, the beavers went back and repaired the first dam! Then they extended the half circle dam across the river channel, and now there are two dams in this complex! I had previously seen this same “recovery plan” at the dam up in Templeton. I want to be able to talk to others about these types of events and see if we are observing the same things. I was so surprised to find out that my sister, who lives in Colorado, is also riding horseback while monitoring beavers. There are some beavers that were relocated by Fish and Wildlife, but the staff doesn’t have the time to monitor those beavers sufficiently, and so my sister is doing that. It’s so funny that my own sister is doing the same thing that I am, also on horseback. She and I are trading notes and learning from each other.

We are in a time of a new movement to protect and conserve beavers, as opposed to killing them off, as was done before, and it is so useful to be able to go to each other and share what we know.

Being a part of the Beaver Brigade beaver dam monitor volunteers connects me with other people who know and care about beavers. And the more that we can learn from others, the more engaged we become with our experience in the river. If you don’t know what you are seeing, you lose enthusiasm. When we learn more about beavers and other wildlife, we look more actively for signals that they are here. We look for signs of recovery and that is very motivating. When folks take steps to protect beavers, such as stakes and caution tape to cordon off the dams while they are being built, we feel hopeful as we see beavers being successful. And knowledge is key. The more people know, the more they seem to slow down and become dedicated observers instead of casual passersby.

Getting all the dams mapped is key to us going forward. Where once there was just one large dam, there are now seven or eight complex dams, and we need to continue to develop our methods of documenting all the dams we are observing. And, for any folks that are interested in doing beaver dam monitoring on horseback, it’s important to know that you have to have the right horse for this work. For example, I’m frequently riding my horse up to her belly in water; a lot of horses can’t handle that. A calm and cooperative horse leaves me safer out there. With the wrong horse, you could be hurt or cause harm.

Thank you Ann for the opportunity to see the River from the heights of a horse, through our conversation. Folks that are interested in joining a warm, friendly and enthusiastic team monitoring beaver dam habitat, on foot or by horseback, should know that in the spring or summer months of 2025, we will initiate a second cohort of volunteers. Volunteers visit beaver dams weekly, documenting the status of the dams and alerting Beaver Brigade staff of any issues and gather monthly in a virtual meeting to share their experiences with each other and exchange ideas and support. All training and ongoing support is free and open to curious nature lovers. Please contact info@slobeaverbrigade.com for more information.